Lowe's New Rounds of Layoffs May Be of Interest to the SEC

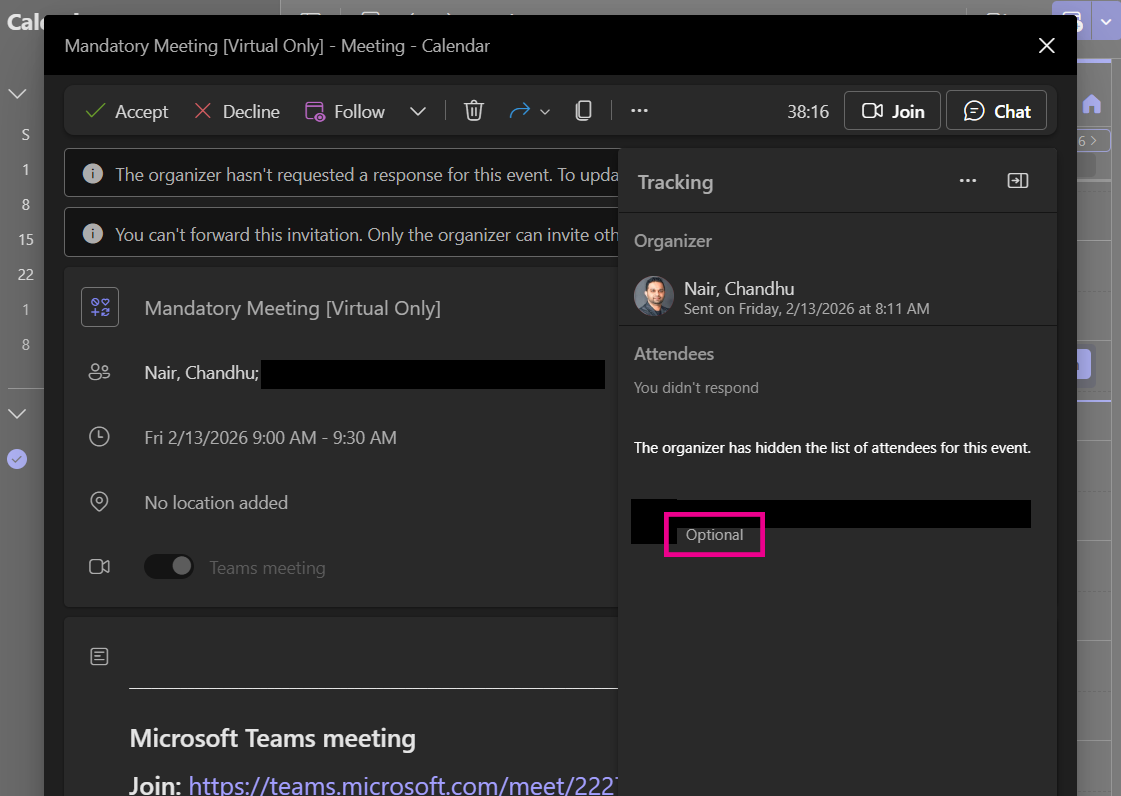

On Friday morning, Lowe's Companies eliminated roughly 600 technology jobs. The affected workers – product managers, designers, researchers, QA analysts, and store operations – were notified through a pre-recorded call attached to a calendar invite where all attendees were marked "Optional."

Some didn't attend. They discovered they were unemployed when their laptops stopped connecting. Within the hour, they were locked out of every system, including the one where the notification had been posted.

No written notice was provided. Employees were told something would come in the mail. The support email provided on the termination call – godbalesupport@lowes.com – was misspelled. Lowe's stock closed at an all-time high the day before.

Within hours, the laid-off workers had built their own Slack channel. It filled quickly with grief and a picture of what had actually happened. Entire teams had been dissolved with no transition plan. A brand new application that had launched the previous week was left with only two people. A training supervisor was pulled from an active new-hire class to be told the position no longer existed. One employee described losing a Pro analytics platform they'd built from the ground up, calling the institutional knowledge walking out the door "incalculable."

These were not underperformers being trimmed. Multiple employees confirmed the cuts had nothing to do with individual evaluations. As one wrote: "This was all based on artificial reasons to cut costs. Nothing to do with our individual performance." What they described was not a surgical restructuring or strategic initiative, but rather a liquidation of assets – fast, chaotic, and executed with no apparent plan for what comes next.

Lowe's official statement, provided to WCNC Charlotte, said the layoffs would "better align our resources to support our stores and the associates who serve customers every day." CEO Marvin Ellison has separately told media that corporate jobs are more at risk from AI than front-line work. "AI isn't going to fix a hole in your roof," he said.

But the teams that were cut on Friday directly contradict that narrative. Among the eliminated positions were store operations technology teams – the people who built and maintained the software that store associates use every day. AI infrastructure teams were gutted, including engineers supporting tools that had just been launched. The PROvider Experience Group, which supported contractor-facing store operations, was hit. Quality assurance teams that tested store-facing applications were dissolved. If the goal was to better support stores, Lowe's just fired the people who were doing exactly that.

That chaos is the first sign that something deeper is wrong.

Companies that are operating from a position of strength do not gut entire product teams in a single morning without a succession plan. They do not leave a newly launched application without a support team. They do not cut the people mid-sprint and hope the work finishes itself. What happened at Lowe's on Friday had the character of an emergency – a move made because the alternative is worse.

To understand what that alternative might be, you have to understand how Lowe's has been accounting for the people it just fired.

Under an accounting rule called ASC 350-40, companies that build internal software can capitalize the salaries of the product teams doing the work. In plain terms: instead of reporting an engineer's $150,000 salary as a cost that reduces this quarter's profit, the company records it as an asset – like a piece of equipment – and spreads the expense over several years. The quarterly earnings look better. The balance sheet looks like the company is investing in technology. Wall Street rewards this.

Lowe's, like many technology-investing companies, capitalizes a portion of its software development labor. The question is how aggressively – and what happens now that the workforce is gone?

The problem is, when the product teams disappear, the projects they were building don't get finished. Under the accounting rules, if a software project is abandoned, the capitalized costs have to be written down immediately – a charge that hits the income statement all at once. If Lowe's had been capitalizing a significant share of its tech labor, and those projects are now sitting unfinished with no one to complete them, the company would be facing a wave of impairment charges that could reveal just how much of its reported "investment in technology" was really deferred salary expense.

Unless someone else can pick up the work.

When Seemantini Godbole joined Lowe's as Chief Information Officer in 2018, the company's Global Capability Center in Bengaluru, India employed about 1,000 people. Today, that number exceeds 4,700. As American headcount shrank through successive rounds of layoffs in 2023, 2024, 2025, and now, 2026, the Bangalore office expanded in lockstep. Lowe's India Private Limited reported revenue of ₹2,120 crore last year, a 15% annual growth.

If the Bengaluru team inherits the abandoned American projects, Lowe's can argue the work is "continuing" and avoid writing down the capitalized costs. The balance sheet looks clean to shareholders. But the economics have changed entirely: a $150,000 American salary has been swapped for a $25,000 Indian salary, while the capitalized asset remains on the books at the original valuation. The financial statements would tell investors the company is making a sustained investment in technology. The reality is that the investment was gutted overnight and rebuilt at a fraction of the cost, with the savings flowing to the bottom line on a delay.

But more than aggressive accounting, the chaos of Friday's layoffs may point toward a more damning fact: the business is shrinking.

Revenue peaked at $97 billion in fiscal 2023. By fiscal 2025, it had fallen to $83.7 billion – a 14% decline in two years. Net earnings dropped from $8.4 billion to $7 billion, a 17% decline. The company posted eight consecutive quarters of negative comparable sales before barely breaking even – and the recent positive numbers were driven by hurricane rebuilding and Pro contractor business rather than organic growth. The company's own filings describe "continued near-term pressure" in its core DIY discretionary segment. Customer transactions fell 3% in the first nine months of fiscal 2025.

And yet, the stock hit all-time highs.

There is a gap between a business that is actually contracting and a share price that suggests it is thriving that is currently unaccounted for. Lowe's stock is rising because Wall Street is rewarding Lowe's margin expansion. If the offshore team inherits capitalized projects, the cost reduction from the labor swap would not appear as an immediate expense reduction — it would be embedded in the amortization schedule of existing assets. Whether this is happening, and whether it's being disclosed appropriately, are questions the company's auditors should be examining.

A successful business doesn't gut a team that just launched a product if they have a plan. A successful business doesn't leave entire functions with zero coverage if you're executing a deliberate transition. The evidence suggests that Lowe's did these things because their numbers needed to change now – when revenue is falling, customer traffic is declining, when the salaries being capitalized can no longer be justified against the returns the assets are generating, and the fastest way to close the gap between what the balance sheet says and what the business is actually doing is to eliminate the cost line before auditors start asking why the assets aren't producing.

The timesheet change raises its own questions. One week before the layoffs, Lowe's altered its timesheet and reporting requirements. Timesheets are the system employees use to log how their hours are split between capitalizable development work and non-capitalizable maintenance. The timing invites an obvious question: was Lowe's preparing to reclassify how it categorizes labor costs in advance of eliminating the labor? Was it restructuring the data so that the transition from domestic to offshore teams would look seamless in the next filing? The company has not said.

There is another dimension to the accounting question that deserves scrutiny: how Lowe's was measuring the value of the software its product teams were building. Employees with direct knowledge of internal reporting describe a culture of back-of-the-napkin math – rough estimates presented as rigorous analysis. The company used metrics like "Likelihood to Recommend" scores to demonstrate the success of internal-use software tools. But LTR is a measure designed for consumer products with competitive alternatives. When the software is an internal tool that employees are required to use (known as a captive audience), a high recommendation score measures nothing. Employees who reviewed internal reports describe seeing these vanity metrics dressed up as performance indicators in presentations to leadership. Meanwhile, another employee who actually benchmarked several applications using approved metrics found nearly all scores for products were failing. It raises the question of whether the analyses justifying capitalized software assets – the kind an auditor might want to see – were based on reliable data. If the assets on the balance sheet were being justified by metrics that don't measure what they claim to measure, the gap between reported value and economic reality may be wider than even the labor swap suggests.

And yet, an allegedly "successful" company with stock prices at all-time highs, cut 600 people with no plan, no written notice, and no explanation that withstands five minutes of scrutiny.

Recognizing the pattern at Lowe's requires understanding what happened before Godbole arrived.

Before Lowe's, Seemantini Godbole served as SVP of Digital and Marketing Technology at Target, where she held senior technology roles from 2013 to 2018. During her tenure, Target implemented major corporate workforce reductions, including the 2015 restructuring that eliminated over 3,100 corporate positions. In September of that year, Target cut another 235 U.S. headquarters positions while simultaneously cutting 40 at its India IT Center, publicly describing the action as a "transition to an agile technology development and support model."

Target's Indian GCC continued to grow throughout Godbole's tenure and after her departure – reaching 5,693 employees, with revenue growing at 34% annually. In October 2025, Target cut an additional 1,800 U.S. corporate roles. Within two weeks, Modern Retail reported, the company posted over 200 new positions – 82 of them in India, including engineers, product designers, and data analysts in the same functions it had just eliminated domestically. Laid-off Target employees reported bluntly that the plan was to offshore all of tech, engineering, and security.

Godbole joined Lowe's as CIO in 2018. A pattern similar to what had occurred at Target followed.

In late 2023 in a prior round of layoffs, Lowe's eliminated its U.S.-based IT Service Center team – the tier-one support desk workers who answered the phone when Lowe's employees needed technical help. Queen City News reported the story at the time. Affected employees, some of them veterans, confirmed the jobs were being sent to the company's Bangalore office. The American help desk was replaced by an Indian help desk.

This Friday, Lowe's cut the Indian help desk too – allegedly because there are now not enough American workers to support. The company offshored the help desk, then offshored the product teams, then eliminated the help desk because there was no one left to help.

This offshoring operation was underway before ChatGPT existed. The GCC was scaling in 2019, 2020, 2021 – long before any executive had a chatbot to point to. One laid-off employee put it clearly: "I think AI and RTO are the cover for the business expenditure angle." The industry-wide invocation of artificial intelligence as a justification for cutting headcount is, in many cases, a convenient narrative layered on top of a labor arbitrage that was already in progress. AI is not taking these jobs. The jobs have been systematically moved to a country where the labor costs 80% less.

Return-to-office mandates serve the same function. Lowe's pushed RTO as a business imperative against all industry benchmarks. Some employees complied, uprooted their lives and relocated to Charlotte, dealt with an office that did not have room for them, only to be laid off anyway this Friday. Former employees stated their Workday profiles – the internal HR system that tracks employee location and status – had not even been updated to reflect the move. No one who was working remotely was offered the opportunity to relocate before being terminated.

There is a dimension of this story that extends beyond Lowe's balance sheet and into a question that policymakers have so far failed to ask.

America's critical infrastructure runs on software. Banking, healthcare, energy grids, logistics networks, defense contracting – all of it sits on a technology layer that has to be built and maintained by someone. When the people who build and maintain that layer are systematically moved to another country, you have created an economic problem, and also a dependency.

The U.S. government recognized this with semiconductors. The CHIPS Act exists because policymakers understood that outsourcing chip fabrication to Asia created an unacceptable strategic vulnerability. No one has recognized the same thing about software. Chips are useless without the codebase that runs them. That code is increasingly being written, maintained, and controlled from India.

Lowe's presents itself as an American home improvement retailer. Yet its domestic technology workforce has been systematically reduced while its offshore operation has grown nearly fivefold — a pattern that raises questions about whether the company's public commitments to American workers and communities align with its operational decisions. And Lowe's is not doing this in isolation. Walmart, Target, Home Depot, JCPenney, IKEA, Albertsons – all operate GCCs in Bengaluru. India's GCC sector now employs 1.66 million people across 1,580 centers. The Indian government projects this will reach 2.8 million by 2030. That growth represents a transfer that makes U.S. business vulnerable.

The offshoring playbook has a shelf life. Labor costs in India are rising. The talent advantage narrows as demand increases. The companies executing this strategy are borrowing against a future where the arbitrage no longer works – and when it stops working, they will have neither the domestic workforce to fall back on nor the institutional knowledge to rebuild. They will have optimized themselves into a corner, having traded long-term resilience for a few years of better margins.

The WARN Act requires that employers provide 60 days' advance written notice before a mass layoff – or provide pay and benefits in lieu of notice. Lowe's appears to be taking the second path, telling employees they'll remain on payroll through April 19, roughly 65 days from the layoff date. Pay in lieu is a recognized compliance mechanism. But it doesn't waive the obligation to notify state officials, and as of Friday evening, no WARN filing appeared in North Carolina's public database. On the call, employees were told one "would be" filed – future tense.

The notification itself was a pre-recorded message on an optional calendar invite, delivered the morning of the layoff with no prior warning. No individualized written notice was provided. Some employees did not attend the call and were not separately informed. All were locked out of company systems the same day, including the platform where the notice was delivered. As of this writing, no affected employee has reported receiving written documentation of any kind.

Whether this meets the procedural requirements of the statute is a question for employment lawyers. Whether it is how a Fortune 50 company should treat the people who built its digital infrastructure – that question answers itself.

This investigation is ongoing. In the coming weeks, we will publish a detailed analysis of Lowe's software capitalization practices benchmarked against Home Depot and peer retailers, using seven years of SEC filings. We will trace the inverse growth curves of U.S. tech headcount and Bengaluru GCC headcount, filing by filing. We will examine whether executive compensation is tied to the metrics that improve when domestic workers are replaced with offshore labor. And we will continue to document how the people who built Lowe's technology were discarded the moment the balance sheet needed them to disappear.

Lowe's was contacted for comment on February 13 and provided with specific questions regarding its software capitalization practices, the timesheet changes, the Bengaluru GCC transition, and the treatment of employees who relocated under the return-to-office mandate. The company has not yet responded. This article will be updated to reflect any statement from Lowe's in full.

Updated February 15th for clarity.

If you are a current or former Lowe's employee with information relevant to this investigation, you can reach out on Signal. Source confidentiality will be protected.

If you were affected by the February 13 layoffs, consider consulting an employment attorney before signing any severance agreement.

The McClure Standard is an independent investigative publication. All claims are verified through multiple sources, public filings, and documentary evidence before publication.